The ways in which we interpret public space and its contents vary considerably across the globe, as it is occupied by a myriad of inherent and overt visual content. I am a big fan of cities and societies that encourage a sense of the proletariats active ownership of public space. Large city squares, parklands and winding alleyways all have the potential to encourage active loitering; places where people can just hang out and experience or create experiences whereby the simple act of just being remains central.

Invitations of varying demographics to consistently shift the use and focus of space are amongst the mechanisms that can facilitate this. I would cite Melbourne’s Federation Square as being an affirmative mode of providing a space conducive to active loitering; it is a place that dynamically encourages a broad cross section of social groups to activate and occupy itself. Surveillance cameras, jack boots and paddy wagons are components of public space that discourage active loitering, perhaps by activating a sense of fear and oppression, reminding users of the space that there is an external power keenly monitoring and maintaining a status quo, either declared or obscured.

The visual cultures encountered in everyday urban existence draw invaluable interfaces between the associations of visual data required for negotiating daily life and visual data that affords us opportunity to critique it. The majority of visual data commonly found in our contemporary urban environments is presented via a necessity for promotion, with the final outcome being the individual’s ascendance into capitalist nirvana. Some of the visual data we encounter publicly is art; with portions of this being mediated variously through arts organisations, not-for-profit groups, funding bodies and that which is non-mediated; applied by the discerning individual.

Art that is presented publicly is vastly different from art presented inside galleries. Often public artists will employ media such as postering and public moving image that are already synonymous with advertising and public broadcast, These mediums can offer more potential than traditional art forms such as painting or sculpture. Often with these mediums viewers are ambushed by artists, finding themselves in situations where they begin the process of interpreting an artwork before they even realise and in this way are not inhibited by the guilty obligation that they should be interpreting a piece of art.

A case in point is Zina Kaye’s recent Bondi Junction shopping centre intervention, Hyperplex. Somewhat a reinvention of Jenny Holzer’s 80’s LED works (though I question whether many shoppers/viewers were aware, cared or should care), Kaye’s suspended LED banners spewed forth hypothetical musings on international politics, life and pop culture gossip. I wonder if passing shoppers stood bedazzled, stunned as if injected with a big ol’ shot of digital public art. Surely everyone was familiar with the medium, having seen them on the counter at their local servo or kwik-e-mart; seeing but wondering “Why doesn’t it tell me the time or date?”, “I wonder if that’s the new Keno screen?” amongst “What can I buy next?”.

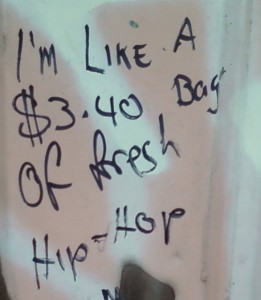

Public interventions can be subtle, overlooked and blend seamlessly into the juggernaut of visual stimulation we receive as participants in urban life. At times they are singled out as bad visual culture or a pollutant, though subjectively as such. Graffiti can be ascribed to each of these categories – as can advertising. Sometimes graffitist’s co-opt public technological mediums such as LED screens and illuminated signage – to ends which perpetuate more the socio-political action of graffiti, rather than the specific content of an outcome. The act of appropriating public and corporate mediums is absolutely vital in contributing to dialogues of cultural ownership and deconstruction. I believe that modest underground culture jamming, often overlooked by mainstream cultural institutions are absolutely critical in contributing to our contemporary visual culture discourse. Enter stage right… Graffiti Research Lab (GRL). GRL base their actions upon open access technologies, employing mediums freely accessible to a large demographic and purposefully inviting the public to participate in their works. Night owl activities such as mega-scale laser projections and en mass magnetic LED throwie sessions form the spine of GRL’s populist ouvre. Their exploits are definitively aligned with graffiti… writing on other people’s property, reclaiming public space and clandestine adventure.

Public interventions can be subtle, overlooked and blend seamlessly into the juggernaut of visual stimulation we receive as participants in urban life. At times they are singled out as bad visual culture or a pollutant, though subjectively as such. Graffiti can be ascribed to each of these categories – as can advertising. Sometimes graffitist’s co-opt public technological mediums such as LED screens and illuminated signage – to ends which perpetuate more the socio-political action of graffiti, rather than the specific content of an outcome. The act of appropriating public and corporate mediums is absolutely vital in contributing to dialogues of cultural ownership and deconstruction. I believe that modest underground culture jamming, often overlooked by mainstream cultural institutions are absolutely critical in contributing to our contemporary visual culture discourse. Enter stage right… Graffiti Research Lab (GRL). GRL base their actions upon open access technologies, employing mediums freely accessible to a large demographic and purposefully inviting the public to participate in their works. Night owl activities such as mega-scale laser projections and en mass magnetic LED throwie sessions form the spine of GRL’s populist ouvre. Their exploits are definitively aligned with graffiti… writing on other people’s property, reclaiming public space and clandestine adventure.

The largest impact of technology upon graffiti has been the availability of information and communication. I recall, at the ripe age of 13, being turned on by the Australian centric graffiti journal, HYPE. In the back of the mag there were postal addresses of fellow artists keen to exchange photographs. One printed magazine and snail mailed prints were the way in which I found out about interstate works. Now graffiti makers and fans have access to highly organised websites such as 12oz Prophet and Stencil Revolution which make it almost impossible to exhaust the amount of images, moving images and articles available online. This is further discussed in Caleb Neelon’s article.

There are some opportunities for damage inclined vandals to vent and splash their creative juices virtually – at least there are to the games inclined masses outside of Australia. As discussed in Katherine Neil’s piece, the Australian Office of Film and Literature Classification has judged Mark Ecko’s Getting Up, a game based on the glorified actions of a graffitist, to be unsuitable for our local audience, citing its desensitisation of vandalism as inappropriate and even dangerous. Preparing one’s mind for true to life war scenarios via headset driven LAN rooms illuminated by glowing screens would seem, however, perfectly fine.

Huge, public, kick-ass digital screens can be both awesome and overwhelming, limited only in potential by their projected content. Charity Bramwell’s 2007 project, Caught on Tape, combined digital representation and street oriented artists via a curated program of video works presented over the period of a month at Melbourne’s Federation Square Big Screen. This was an extension of Bramwell’s continued facilitation of explorations into intersections of street art, the urban environment and experimental visual art. Manchester’s Urban Screens project, reviewed in this issue by Melinda Rackham, was devoted to dialogue and experimentation within the realms public screen culture. This examination and critical discourse of a burgeoning international medium is crucial in maintaining as much democratic accessibility to the content of these public broadcast tools.

Physical graffiti and its associated actions are largely illegal whereas negotiated public art can successfully bridge the gap between the interventions, the owners of space and their inherent values. Maybe Shibuya’s towering digital prowess could be co-opted into one unified creative experience, sponsored by world peace via Japanese harmony, mixed with a little hippy social inclusiveness – or maybe the world’s largest urban and technology centric art space could activate unified respect and love between each human being an the next. Perhaps that’s what it already is.

James Dodd

James Dodd has successfully exhibited across Australia in artist-run spaces, institutions and commercial galleries. James is currently a full-time Masters candidate at the South Australian School of Art, Uni SA and is represented by Ryan Renshaw Gallery, Brisbane.

Read More

http://james-dodd.blogspot.com

Watch More

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 Australia.

[...] Active Loitering – James Dodd. ANAT Filter 67. [...]