Big screens give us those grand spectacles that don’t seem to stuff back down to the dimensions of everyday life: an imaginary car crash, the curve of a planet, wide-screen love. The vast unfurling networks of mobile phone communities prove that when it comes to the dimensions of a screen, size alone does not matter. The tiny portal of a mobile phone screen is a disguise for a unique platform. Behind its miniature display one may organise nomadically networked events, narrowcast interactive short stories and globally connect gamers on the street with virtual players online.

Mobile Journeys is a national initiative devised to encourage the development of creative mobile phone content. One of its many achievements has been to promote critical debate amongst artists, consumers and developers, which addresses how mobile telecommunications may affect our cultural and social future. Throughout 2005 Mobile Journeys conducted a series of master-classes, public workshops and professional forums throughout Australia within which participants learnt about the production and delivery of mobile phone content, and the sociological impact of mobile telecommunication. In stage two, fourteen artists were commissioned to produce new works for videophones, resulting in a series of games, networked events, interactive installations, animation and video. Eight of the fourteen commissioned Mobile Journeys works will be on display at the State Library of South Australia during March as a part of Media State.

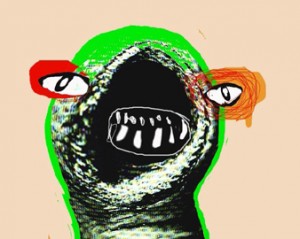

Liberv vel Reguli!, Ian Haig, 2005

One such work is Ian Haig’s Liberv vel Reguli!, a hysterical sequence of animated drawings perching between a paranoid revolt against mobile phone technology and a techno-occultist’s feverish embrace. The work’s title, which roughly translates as “The Mark of The Beast”, is commonly perceived to be an ancient Latin invocation of Satan, although was employed by the likes of Aleister Crowley (and other magicians since) as a ritual incantation that appeals to the divine powers of the Ancient Egyptian god, Horus. Haig’s crudely effective paintings of human worms, and Revelations-style messages strobe within the tiny screen like psychic snapshots from the mind of someone who goes to sleep wearing a tin-foil helmet. Making reference to the notion of “possessed media” whether Haig is attempting to possess or exorcise one’s mobile phone is not clear.

In a work titled Breaking Up, Tina Gonsalves voyeuristically re-constructs a mobile phone conversation between two lovers as they drift in and out of range. Signal loss is a poignant and simple allegory of a relationship breaking up as the level of communication degrades. Gonsalves has cleverly collaged the couple from clear photographic images into Dada-like portraits of their original selves. Gradually the features of each lover’s ‘signal body’ become distorted in mimicry of the conversational tone, reducing the portrait of Hollywood romance into a clash of figures, cut-and-pasted together in a flash of gnashing magazine mouths and dismissive hand gestures.

Watching Chris Fulham’s quiet vignette titled Arrivals is what I had always imagined listening to Brian Eno’s Music for Airports in situ might be like. In a progressive sequence of video stills, anonymous travellers pass through a well-trafficked public space. Some are carrying bags, some are adorned with children. Many are curious, whilst other passers-by glance at the camera or pretending not to notice it. Unlike the flat-screen unity of a camera’s viewfinder, Fulham has deliberately blurred the periphery of the screen, as if to remind the viewer they are watching with their own eyes. The subtle strobing of images blink like eyes in placid observation. There is something dainty and endearing about the act of holding tiny images of people that have been scaled to fit in the palm of your hand. Some viewers have commented that watching people on a small screen makes them as an audience member feel responsible for the characters and their destinies. Such a psychological response could lead to some interesting character development in ‘miniature’ narrative films.

Arrivals, Chris Fulham, 2005

Megan Heyward’s Traces is an assemblage of narrative portraits, recreating the vivid experiences of different people living in the same city. These miniature-screen biopics construct a metropolis of intimate exchanges and grand political gestures, such as making love on Sydney Harbour Bridge, or making statements in twelve metre high red letters on the Sydney Opera House. Such tall and small tales infuse the familiar architecture of Sydney’s CBD with personal histories and local memory. Based upon SMS submissions archived on the Traces blog, these stories were first exhibited as site-specific phone installations around the central business district of Sydney. Each story within Traces is a lushly produced short film, which captures site-specific memories that in a photograph alone would fade.

Meanwhile, back at the pub, a cluster of inebriated sock-puppets peddle beer-inflated tales of a celebrity encounter in Mark Simpson’s Vox Sox. Simpson’s use of backyard puppet-show aesthetics is comically inclusive: much like the sense of camaraderie one gets laughing at a lame in-joke. As anyone who has observed the social mores of a public drinking house could tell you, a local pub and a local beer is the weft and weave of most in-jokes, which more often than not stagger home down the backstreets, making their way into the avenues of gossip and urban legend.

Several works within Mobile Journeys reference the motif of travel more overtly. Ian Andrew’s Urban Passage is a sweet and slightly surreal account of a fairly pedestrian mobile phone conversation between a man commuting on the train home from work and his partner at home. The combination of photographic imagery and 2D animation cleverly shifts the conversation between the physical landscape streaming outside the carriage window, and a mental landscape as it weaves its way into the conversation. Shane Ingram’s Coaster is a conduit for a more sensory impression of motion. Ingram treats the mobile screen as a portal, conducting a seamless amalgam of abstract animation and music. Slight compositional shifts in the music and the animation occur as the viewer passes through metaphysical ‘stations’ within a virtual underground railway.

The Kill Yourself Game, Rebecca Cannon, 2005

Hand-held games are perfect for killing time. Rebecca Cannon and Karen Jenkins have developed a solution for the interminably bored, with a game for the mobile platform titled The Kill Yourself Game. As a gamer, you are treated to an exercise in self-loathing, manipulating your on-screen avatar to slash through the two-dimensional cheer of Happy Town, cutting down clones modelled in your character’s own image. The psychological premise of The Kill Yourself Game is one of catharsis. Inflict enough self-loathing upon yourself in a virtual sense, and (hypothetically) the game will allow you to vent the desire for self-persecution in real life. Such experiential game-play is a daring a provocative psychological experiment that flies in the face of conventional gaming: within which self-loathing and frustration are vented by the destruction of property, monsters and other people.

The mobile phone is a makeshift archive of our interactions with others, a coin purse from which flows a torrent of tiny articles of amusement. At any moment family photos, album covers, animations, games, wallpapers, ring-tones and gossip are Bluetoothed, SMSed and downloaded, enjoyed, passed-on and forgotten. Far from being frivolous, the exchange of such content is as important as sending a postcard or sharing popcorn at the movies: small but meaningful gestures of connectivity. As demonstrated within the exhibition of these works, creative content for mobile devices may also stir profound discourse on the future of communication, technology and society.

Samara Mitchell

Samara Mitchell is a freelance writer, visual arts educator and public artist based in Adelaide, South Australia. She has written for several national arts publications, and has also worked with national and international artists and arts organisations researching alternative applications of emerging technologies.

Read More

http://www.dlux.org.au/mobilejourneys/about.html

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.