Technology captivates us, translating the imagination of science fiction into reality, and reconfiguring the boundaries between function and fantasy.

Communication, health care, lifestyle, mobiles, MP3-s, cameras, organisers: these are our new world and clothing has offered an ideal way to wire us directly into it. Clothing as potential for technology has provoked new explorations into materials, construction techniques and applications before: military uniforms for protection, corsets for enhancement, spacesuits for travel. Today too, designers and engineers, scientists and chemists, artists and technicians are implanting a host of such technologies into what we wear. But jewellers aren’t doing the same thing.

Notwithstanding their different agendas, traditional and contemporary Western jewellers share a similar delight in making seductive, intriguing, crafted pieces to adorn the body. But surprisingly, they are equally limited in their attitude to technology, exploiting it only for its material potential: new uses of traditional precious materials, streamlined design and production methods, honed marketing systems. For example: W. Wittek’s Tension Ring from the German jewellery company Niessing, developed a simple idea to use the tension of a ring-shank to hold a diamond in place. From its debut in 1981, the company resolved its mass production to use a range of subtly-coloured golds, platinum or steel with diamonds and synthetics of all sizes. They’re viewed easily on the internet and sold through a global dealer network. Through technology, then, Neissing successfully combines a traditional product with an inventive spirit. In contrast, hip hop ‘bling’ draws on street cred. It is everyday jewellery blown up into everyday ceremonial jewellery for celebrities. Giant diamond-encrusted watches, crosses, dollar signs and other symbols shine like new money. Technology is readily exploited to customise any product with a ‘nothing’s impossible’ attitude. One piece is about good design, the other is about sheer-indulgence, both are about money with technology as a convenient tool.

So, mainstream trade jewellery still controls the mass market, in spite of at least one major resistance. The Contemporary Jewellery Movement (CJM), lasting from the sixties to the mid-nineties, was the most radical spirit in jewellery history. It interrogated traditional styles, meanings and definitions of jewellery, among them materialism. Contemporary jewellery became an art form that democratised materials. It shunned traditional mass production, and marketing to celebrate the individual maker. Technology was a research tool for new materials and new techniques: anodised aluminium, industrial plastics, electroforming, laminating, injection moulding, computer-aided modelling and so on. In this way, technology helped fulfil the skill-orientated ideals of the CJM and supplement its status as art object. Yet, jewellers still bypassed technology as a strategy for ideas.

Even now, jewellers see technology as functional not ornamental, and they see jewellery as ornamental not functional, so they have not been able to exploit our new technologies as inspirations for their practice. Unlike fashion and industrial design, which developed dialogue between designers and industry to bring experimental ideas to fruition, contemporary jewellery lacks substantial financial resources and ready access to state-of-the-art technologies. There are some signs of change, spearheaded by a handful of universities who are linking art and design students with IT media labs and science technologies [1] but once these students leave, it is more difficult for them to set up necessary connections with multimedia and science research industries, so the results remain limited. The flipside of the problem lies in the interaction between idea, technology and marketing. Jewellers, especially computer savvy makers, readily adopt the internet for promotion and marketing to reach a larger, younger and hipper audience. But, ideas are generally still about style rather than invention. Yet technology is already creating jewellery in the street with every piece of wearable hardware.

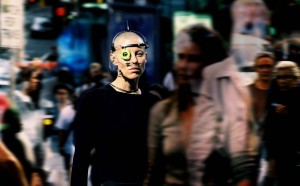

The precedents for wearing technology as jewellery goes back to the eighties. In 1984, William Gibson’s Neuromancer effectively introduced the theme of bodily techno invasion: implanted circuitry, cosmetic surgery, prosthetic limbs, genetic alteration and brain-computer interface. [2] Cyberpunk filtered into street culture and fashion, where it juxtaposed state-of-the-art technology with found industrial waste and holographic fabrics. The fantasies of cyberpunk finally mutated into mainstream culture, where with its interrogations into technology it increasingly reflected everyday life. A year later, in 1985, Donna Haraway’s essay ‘The Cyborg Manifesto’ appeared. [3] A cyborg is a ‘self-regulating organism that combines the natural and artificial together in one system’. [4] It plays out developments in science, technology, postmodern warfare, artificial intelligence and virtual reality. In contrast to the hybrid superheroes of science fiction, it represents the very embodiment of technology and media culture. While science fiction becomes science fact, medical science embraces cyborg-related technologies to open up choices for wearable technology.

The body is being converted into information. High-tech medicine is becoming cyborg medicine. Sophisticated instruments and systems modify and digitise our human being. Technology continues to miniaturise facilitating artificial implants, embedded electrical stimulation systems, exoskeletal prostheses, self-powered cybernetic limbs. But as our bodies are perforated by techno-science, jewellers can adorn it with cyber-jewels. The functional can become ornamental and the ornamental functional in a new fusion of the two.

Indeed, it’s already happening. Some smart objects are now common: the Bluetooth or security key fobs. Some are being tested: watches to monitor blood-sugar levels. Others are in research: electronic name badges to transmit and receive information through filters to the wearer. In other words, wearable technology is the new jewellery. Let me finish with two examples. Charmed Technologies – a MIT Media Lab spin-off – has drawn on industrial espionage and surveillance technology to engineer a symbiosis between technology and fashion, presenting their wearable computer prototypes in staged fashion shows. [5] Their ‘Communicator’ is a wireless broadband internet device activated by voice, a hand-held remote, wireless keyboard and computer screen eyepiece: a virtual office. When worn on the catwalk, it relays the wearer’s vision to the audience via a central computer onto a backdrop screen. [6] The Apple iPod, more specifically the Apple Shuffle, is the ultimate piece of technology jewellery. It successfully marries hip and tech, offering the wearer an individually-programmed world of digital sound in a crisp white device hung around the neck or, now, clipped to clothing: even now, it’s a twenty-first century cultural icon. There’s already smart jewellery, and smart wearers too, and smart jewellers are now only a matter of time.

Susan Cohn

Susan Cohn is a jeweller, working in Melbourne. Her work draws from street culture, technology, music, everyday rituals, as well as acuriosity about objects and processes. Cohn is currently doing a PhD on managed identity and jewellery at College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales.

References

[1] Norman Cherry from the University of Central England in the UK has worked on body modification, “Angiogentic Body Adornment”, which relies on biological engineering. The Royal College of Art in London has a program linked with different technology research.

[2] William Gibson, Neuromancer, New York: Ace Books, 1984.

[3] In Donna Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: the Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991, pp 149-181.

[4] Chris Hables Gray, Cyborg Citizen, New York: Routledge, 2002, pp 2.

[5] Charmed Technologies was founded in 1999 by Katrina Barillovea, an intelligence expert, and Alex Lightman, an MIT graduate with a specialist interest in satellite technologies.

[6] These prototypes have yet to be evolved into fully-functional models.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.