Abstract: This illustrated essay looks at objects/bodies within anatomical museums where the boundaries between art and science are problematic and fascinating: bones formed into the shape of flowers; animal bronchial trees staged as if they were plants; dried human preparations astride galloping horses; wax women and children of haunting beauty and mesmerising terror. The displays are taken from anatomical and pathological collections in Paris, Melbourne, Florence, and Edinburgh. A few of the pieces are well-known. Most belong to collections that are already closed to the public and/or in storage, despite the fact that several have been classified as national heritage collections.

Art and literature here are neither a representation of science nor a tool of visualisation; they are more the deep extension of the bodies of the anatomical museum. The essay suggests ways in which science, art, literature, and history could be combined to create new interdisciplinary exhibits and new intellectual itineraries for the public.

Introduction

This essay will wander briefly in the company of skeletons. The wanderings are through the anatomical museum, on paths that lead past groves of bronchial trees and bone flowers set on glass shelves. Readers who agree to the stroll will watch the dried horseman of the Apocalypse gallop by, blue velvet reins in his varnished hands, and might well wonder where his army of fetal specimens posed on tiny animals has disappeared to. The essay will pause when once-living bodies do themselves; as skeletons sit down to play a pipe or to hold an unheard conversation. Why such a stroll is necessary may not be immediately obvious, for the closures and dusty half-life of historical anatomical museums today rarely make the news. This essay is part of a project to make that loss more theoretically and publicly visible. Despite their slumber, anatomical and pathological museums are fascinating places for critical work on the complex intertwinings of anatomy, art, pedagogy and theatrical staging that were at their core. Some of them could be brought back today as they once were; places where not only physicians but the public could encounter disease, human frailty, and death made as familiar as a small skeleton playing a pipe or flayed men who ride eternally through ancient mansions on their great varnished steeds.

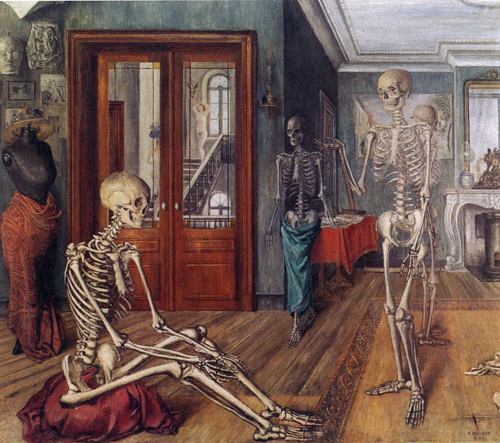

Figure 1 Paul Delvaux, Large skeletons, 1944

From among the millions of real and modeled bodies in anatomical collections, I have chosen a few that show a range of presentation styles and effects: the transformation of fauna (human and animal cadaveric material) into the illusion of flora; the macabre and sometimes whimsical beauties of varnished écorchés (skinned natural preparations), and pathological skeletons set in theatrical poses. The pieces are from collections in Paris, Florence, Edinburgh, and Melbourne. All the pieces reveal spaces in the anatomical museum where the practices of science and the aesthetics of death wind around each other in interesting ways. What this essay can do no more than evoke briefly is what the lonely anatomised dead have inspired; not only scientific knowledge of the body but haunting art and lilting poetry, pleasurably dark stories, and skeletons perambulating through the night (Figure 1).

From points of rest to places of knowledge

Lacking throngs of visitors today, the lonely dead are hardly lonely among their own kind. Anatomical museums often seem to overflow with the dead and their simulacra; full and partial skeletons, models of wax, wood, ivory, and papier mâché of every organ and part, gesticulating hands and walking legs, dried specimens like fragile leaves, thousands of jars filled with gray-hued tumors and aneurisms, fetuses, organs, and skin marked with pocks and blisters. Space crises in the modern institution have often exacerbated the crush of the neighboring dead. In the Musée Dupuytren in Paris, still open to the public today, the skeletons displaying anomalies seem to jostle for space in the overcrowded case (Figure 2), pushing arms and legs in front of each other. Visitors must crane necks to try to peer through pelvic bones or on top of ribs to read the faded cards. The tiny skeletons placed on top of the case seem to survey the room, creating the illusion they have somehow escaped the crowded throng inside (Figure 3). The dead do not lack for company of their own kind. It is space, visitors, and conceptual frameworks for those visitors that the bodies lack.

Figure 2: Musée Dupuytren, Paris. Photographer Marjorie Cabico.

Stephen Bann wrote: ‘There is no reason why a collector’s objects should reach a point of rest within any existing conceptual, or spatial scheme.’ (Bann, 2004; 67) Yet sometimes objects do find that point of rest. Some of the objects in anatomical collections were destroyed. Among them were memento-mori inspired pieces whose esthetic was judged by some museum directors to be too macabre or whimsical to fit the pedagogical objectives, collecting imperatives, or institutional and public tastes of the twentieth or twenty-first centuries. Many of the preparations of the French anatomist Jean-Joseph Sue were destroyed; the few discussed below that remain have somewhat problematic homes either outside anatomy or in closed collections. Many objects are now profoundly cloistered in closed collections or warehouses. The majority of pathological collections are closed to the public, now merely vast warehouses of the anomalous dead.1 Dust mites and mold, a researcher, poet, photographer, or group of medical students shepherded by lecturers, make occasional incursions into their quiet worlds.

Figure 3: Musée Dupuytren, Paris. Photographer Marjorie Cabico.

In Edinburgh, skeletons displaying tuberculosis, scoliosis, and rickets sit in lonely seclusion on their shelves on an upper floor of the museum. (Figure 4). The Royal College of Surgeons is making an effort to bring the pathological collection back to the public.2 How much of the collection might be put on view again is not yet known. While a recent article by Nesi, Santi, and Taddei has brought a few of the pieces of the Pathological Museum of the University of Florence, back into scholarly view, it remains a sleepy collection. (Nesi, Santi & Taddei, 2009; 15-19) Other collections — including the vast collections of the Musées Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière in Paris — are on their way into storage today, their spatial schemes in jeopardy partly because the institutions that host them have lost the belief that conceptual schemes can be made for them today (Figure 5).3 Closed museums and warehoused collections protected by national heritage laws are worth studies themselves. What does an invisible national heritage mean?

Figure 4 : Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Photographer: Navena Widulin

Important critical frameworks exist for anatomical museums, but are uneven in their coverage of the wide range of bodies, displays, and museum types. There is a good deal of excellent work on anatomical models, particularly wax models, including Michel Lemire’s Mortels (1990), Monika Von During, Marta Poggesi and George Didi-Huberman’s Encyclopedia Anatomica (1999), Didi-Huberman’s Ouvrir Vénus (1999), and the 2008 collection Ephemeral Bodies (Roberta Panzanelli, editor). Artistes et Mortels, with its wealth of photographs, now functions a kind of photographic museum of many objects no longer available to the public. Unfortunately, the work is out of print. Chloé Pirson’s book Corps à Corps (2009) has just been published. There is some recent work treating both anatomical and natural history museums, including Stephen Asma’s Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads, and Rosamund Purcell and Stephen J. Gould’s Finders Keepers. It is worth noting however that the nearly 800-page anthology Grasping the Museum published in 2004 does not have a single essay on the anatomical museum.

Figure 5: With permission of the Association des Musées d'Anatomie Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière (AMADOR). Photographer: Marjorie Cabico

The project of which this essay is a part is a project on practical as well as theoretical museology, although the two are not separable. In theoretical terms, it is meant to disturb the Foucaldian Panopticon by catching the disciplinary guards in the moments they turned to stare at intriguing bodies and lost their grip in the pleasures of the gaze. The project is, in part, to bother the disciplines themselves–make them question where they begin and end–and jostle theories that too blithely set meaning within what passes for structure, and knowledge within too readily defined social groups. More than that, it is to allow the public to see giant corporeal fantasies that stretch across the Western social body and practices that weave science, pedagogy, art, and literature into dense networks.

‘It could have been said of him… that he spoke to the eyes.’

In the late eighteenth century, Thouret said of the anatomists Honoré Fragonard and Frederik Ruysch, that they ‘spoke to the eyes’:

Passionate about these anatomical preoccupations, he [Fragonard] imagined, invented pieces that he strongly desired that people would come to see, but he wrote nothing, and it could have been said of him, as it was said of Ruysch, that he spoke to the eyes; for this reason he responded to those who spoke to him of his cabinet: come and see. 4

In the history of anatomical display, speaking to the eyes has been both a compliment and a stinging critique.

It has often been said that modernity was born in the eyes, in the replacement of textual knowledge with the products of observation. Anatomical museums are part of that shift; a celebration of bodies seen and knowledge willed to be made in the spaces of display. Yet that visual speech has often been suspect, as if by speaking to the eyes one risked missing the chance to speak to the mind. Below are several exhibits that speak particularly to the eyes from collections of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They answer the symposium question of whether research into bodies offers an insight into esthetics with a resounding yes. What that esthetics is, how welcome it has been, and how much the tolerance of esthetics in anatomy has varied are more complicated. The stakes involved in looking at the questions now are high. We are losing vastly important collections over fears that art and science are irreconcilable. Major collections, by foregrounding the very tensions they often seek to elide, could produce powerful exhibits.

From the outset, in the seventeenth century, when bodies and their simulacra were displayed in private anatomical cabinets and anatomical demonstrations open to the public, anatomical displays spoke volumes to the eyes. In the Netherlands, Frederik Ruysch posed dead fetuses and babies in memento mori dioramas; entire landscapes made out of human body parts. Decorating his wet specimens of fetuses and babies with bows, lace collars and a silver turban, Ruysch turned the tiny dead in their jars into collectable, intensely artistic anatomical knickknacks. In Genoa, the French physician Guillaume Desnoues had to hastily have a new anatomical theater built to accommodate the nearly 2,000 people (according to his count) who came to see his preparation of a woman and fetus that he had laboriously transformed into a mixture of cadaveric human and wax model. Desnoues escorted visitors through his private cabinet, thrilled when a visitor thought he could smell putrefaction in what was only wax, or mistook a wax head for a real severed head, the effect enhanced by a drop of wax “blood”. As far as we know, none of Desnoues’s models exist today.5

Anatomical museums were born, in part, in competitions over the artistic dead and their images: in art as a mastery over a primary material which included flesh and bone; in demonstrations of expertise; in staging, playful trompe l’oeil effects, fanciful decorative elements, and calls to the senses. Those calls to the senses did not always fit later tastes. The nineteenth century would work through the collections, accepting some art within its collections, especially that which could be seen as sculptural. The beautiful recumbent wax nudes, writhing écorchés, and standing Florentine figures often modeled on classical sculptures have places of honor in museums throughout Europe.6 So do Auzoux’s large papier-mâché bodies, which sometimes dominate museum spaces like giant sculptures. A giant Auzoux model in the entrance towers over visitors to the Musée de la Médecine at the Université Libre de Bruxelles.

Much of the remainder of art in the anatomical museum, especially memento mori art, became problematic and was destroyed or permanently shifted out of the discipline of anatomy. In eighteenth-century France, Jean-Joseph Sue’s collection included memento mori anatomical pieces in the line of descent from Ruysch’s models. One piece from the collection, cataloged today as a “Macabre altar” ["Autel macabre comprenant une momie et trois squelettes de foetus humains, fin du XVIIe siècle"] was donated by Sue’s son in 1829 to the Musée des Beaux Arts for its course on “picturesque anatomy” ["anatomie pittoresque"]. It has three fetal skeletons, one holding a scythe and the other a stylus with a feather, and a mummified fetus. Verses by Virgil and Malherbe – the latter’s work is a poem on the dead of a child who had lived only for a day – frame the tiny figures. Moved from the realm of anatomy into that of picturesque art-anatomy, the piece survived in part because of its reinscription into the disciplinary space of art.7 Much of the rest of Sue’s collection was destroyed.

Figure 6: Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology, Melbourne. Reproduced with permission.

A spectacular piece attributed to Sue (perhaps Sue the second) is maintained today in Melbourne, in the Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology, from the collection of George Britton Halford. It is the small skeleton of a man (Figure 6). The lower ends of the thigh bones are blended and the skeleton displays a single knee joint, lower leg and foot. Staged sitting on a small wooden base, the skeleton is staged as if it is playing a pipe held delicately in its bony fingers. The accompanying text board reads:

The remarkably deformed skeleton is the property of the Melbourne University. It was purchased in Paris in 1862 by Mssrs. Raginal and co. and is stated to have been prepared by the late Dr. Sue. The being whose skeleton is here represented, with pipe in hand, is said to have played the instrument on the steps of one of the churches of Paris, and to have attained the age of 21 years.

The preparation is part of anatomical museum history that once kept and retold the stories of at least a few of the real people who had become its specimens. The skeleton playing a pipe is not a phenomenon merely of pathology that studied the anomalous but of collection that reveled in the remarkable. Museum directors once peppered their collections with remarkable, poignant, and even mirthful pieces that sometimes bring a small smile amidst the hordes of partial bodies flayed, dismembered, boiled, sliced, pickled, and containered.

Figure 7: Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology, Melbourne. Reproduced with permission.

Just down the hall in the second room of the museum, two other skeletons are posed in a large class case (Figure 7). Seated as if in conversation, they turn slightly away from the visitor, seemly more interested in each other. One skeleton lowers its head, resting its hands on its thigh bone. Its interlocutor, arms crossed and legs stretched out and gently bent, seems at ease. The skeletons display the rare disorder Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva and the text board explains for the medical students, that the gene for the disorder was discovered in 2006 in the Pennsylvania School of Medicine. The skeletons are certainly pathological specimens displaying the symptoms and sequels of the very rare disease; the extra-skeletal bone formations caused by the ossification of tendons and ligaments and the characteristic skeletal anomalies including an abnormality of the big toe. Yet more than examples of the disease, they are a staging of the disease, with a poignant, ironic note, for those with Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva may have difficulties with both speech and movement, due to the ossification of their joints (Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva). Their gentle post-death conversation in a case contrasts with the difficulties the living owners likely once had.

If one is lucky enough to be alone in the two museum rooms, it is tempting to listen for the strains of music coming out of a pipe held in small hands or bits of the conversation between the two skeletons seated in their glass case. The Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology has perhaps two of the most beautiful pieces of esthetic, evocative anatomical staging remaining in the world today. Signs posted every few feet remind visitors that they may not take photographs of the displays and that they are under surveillance themselves. It is a place of overlapping gazes of curiosity, science, and an occasional rather remarkable playfulness no longer visible in many collections and not accessible to the public in Melbourne today. Passersby in the halls of Melbourne University can catch no more than a partial glimpse of the pipe-player through the museum windows.

Figure 8: Pathology museum, Department of Human Pathology and Oncology of the University of Florence. Photographer: Brook Ellis.

Artful construction, play, mirth, and poignant reminders of death abound in anatomical collections and are part of currents that run deeply through anatomical museums. It is perhaps anatomy as cool, serene, factual knowledge of the body that is the illusion created, as collections progressively divested themselves of their more artful pieces and moved pathology more and more into the realm of professional/institutional/closed knowledge. In Florence, in the now-closed pathological collection at Careggi Hospital, human leg bone preparations fan out like flowers. Whatever they might show about bones (there is no label), that knowledge vies with their esthetic power as artful manipulations of legs (Figure 8). Hidden on a lower shelf, they offer almost pretty, playful botanical-like moments among the many remarkable pathological specimens: the rare fetal specimens, some of their heads now poking out of formaldehyde in their pretty nineteenth-century jars; and the many waxes. There are horrifying spectacles of faces devoured by cancers and ulcers or deformed by giant tumors and bodies covered by skin diseases, growths, eruptions, and cysts. The life-sized figure known as the “leper” (although that is not the disease depicted) lies quietly in his case and few today see the lovely young wax girl who wears a delicate lace cap, her face ravaged by scrofula.9

Figure 9: Bronchial trees/Arbres bronchiques. Musée de l'Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort. Photographer: Marjorie Cabico.

No matter how much memento mori, esthetic, playful, and whimsical elements were weeded out of museums in the twentieth century, pockets of them remain, reminding us of older, complex visual practices that where part of the collections. In the Musée Vétérinaire d’Alfort in Paris, small groves of bronchial trees sit on shelves (Figure 9). Bronchial trees are the correct term for these structures which belong to a cow, mule, horse, donkey, sheep, dog, pig, cat, rabbit, guinea pig, and goat but the display is anatomically and logically incorrect, unless of course all the animals were lying on their backs, or better yet, standing on their heads. Bronchial trees extend down into body cavities, not up into the air. While the bronchial trees in the veterinary museum do provide a sense of comparative anatomy, they are also a visual pun. Bronchial trees set like their vegetable counterparts, become artistic works.10 Bronchial trees and bone flowers bridge the three categories of earlier cabinets of curiosities. As zoological material, the cadaver is naturalia. As an object worked with skill and artistry, it functions as artificialia, much like an elegant carving, or a piece of sculpture. The rarity of their preparations turns them into mirabilia.

Flayed men on horses: the pleasures and problems of staging the dead

‘Daylight does not lend itself to terror’ Guy de Maupassant (2004; 452)

Some of the most unruly bodies of anatomy have survived in what is left of Honoré Fragonard’s eighteenth-century collection of dried and varnished natural human and animal specimens. It has drawn visitors from around the world from Fragonard’s day until today. The display is, in a fascinating way, both included in and excluded from the Musée Vétérinaire d’Alfort. It is in the same building, visited with the same ticket, approached through the large museum collection, but bracketed off from it by a set of translucent glass doors and by a vastly different presentation style. The major veterinary collection with its many animal skeletons, prepared organs, and straw-stuffed “monsters” in glass cases is naturally lit through large windows. Surrounded by stone and glass, the pieces inhabit the coolly pale world often inhabited by both anatomical and sculptural collections.

Beyond the doors to the Fragonard collection lies an entirely different display world. The Fragonard collection is dark and moody, spotlights dramatically highlighting the curves of varnished figures. Fragonard’s écorchés (flayed figures) are real dried and prepared humans and animals. The museum’s web site makes a distinction between the pieces the museum classifies as pedagogical and those that are ‘in theatrical attitudes’, establishing pedagogy and theater as impossible bedfellows: ‘The pedagogical preparations are devoted to studies of a single precise system; their rigor and the absence of staging readily distinguish them from the other flayed figures, fixed in death in theatrical attitudes.’ 11

Yet the museum chose to stage the pieces in ways that increase the very effects with which they seem uncomfortable. The Fragonard écorchés are ludic, involving erudite plays of references, and narrative lines that were once strong. The standing male, holding the jawbone of an ass in his right hand, is Samson slaying an invisible Philistine who would be standing just behind the observer. The most famous is known as the ‘Horseman of the Apocalypse’ (Figure 10). It is a flayed, wax-injected, dried, and varnished human on a flayed, wax-injected, dried, and varnished horse. The props–blue reins and a whip–have recently been restored. The museum’s web site describes some of the still-missing elements from the original display: ‘The macabre effect of the scene was intensified by small human foetuses riding sheep or horse foetuses gathered around the ‘Horseman of the Apocalypse’, as if they were his army.’ (Musée Véterinaire d’Alfort, ‘The Ecorchés by Fragonard’)

Figure 10: Musée Fragonard, Musée de l'Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort. Photographer: Marjorie Cabico.

The spectacle of fetuses of the Apocalypse preceding the great horse riders (for there used to be more than this one), velvet or silk reins in their hands, was a masterpiece of not only anatomical preparation but of imagination, with plays of reference that relied on a viewer with a dose of culture for full effect. The fetal parade is absent today and I wonder if tiny fetuses on sheep still ride through the attics or armoires of French châteaux. The museum does have several fetuses that still dance today, but they dance in their own company on a shelf in another case. There seems to be a reticence about reestablishing the original anatomical spectacle.

Not everyone appreciated the collection. In 1783 the German naturalist Heinrich Sander, blamed the Fragonard preparations on the generally frivolous nature of the entire French nation: ‘Note how the frivolous spirit of this nation comes out, even when it is trying to do something truly grand and noble and when its playful and lighthearted nature ought to take a back seat.’12 (Lemire, 1990; 171). Several years later, another German, the veterinary surgeon Rumpelt voiced a similar complaint: ‘All the preparations displayed in the cabinet satisfy only sight; few of them can be used to demonstrate new truths… everywhere there is elegance which is not instructive.’13 (Lemire, 1990; 171) Sander and Rumpelt distrusted sight infused with pleasure, thought scientific grandeur at risk from elegance.

Both star, and in some way, unincorporable excess of the museum, the Fragonard pieces are set in a space designed to resemble a natural history cabinet. But that cabinet (Figure 11), disappearing into the penumbra beyond the spotlights, is difficult to even notice before one walks past the écorchés, and even more difficult to concentrate on, for it is hard to take one’s eye’s off the écorchés. The message encoded in the museum structure is hard to miss; the Fragonard écorchés belong to the world of cabinet collecting that existed prior to the modern museum, to the imaginary of an “anatomical virtuoso” that today needs to be bracketed off, even simply by translucent glass, from the other world of anatomy.14 The Fragonard collection is too important historically to disappear today. Corporeal spectacles designed for the eyes also help us document what drew the bodies of real people into institutional spaces and movement around cities. They are part of the still understudied histories of tourism and urban life.

Figure 11: Musée Fragonard, Musée de l'Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort. Photographer: Marjorie Cabico.

The bronchial trees and bone flowers, the unusual skeletons that amuse the viewers with their pipe playing or who gallop by on great varnished steeds, cannot be dismissed as museological or individual idiosyncrasies. They are part of a complex and elaborate world of bodies and death that was elaborated from the eighteenth through the early twentieth centuries. Bodysnatching, grave-robbing and the unreflective use of bodies from the margins of society have been well studied. Gone almost without study at all are facets of that history that also reveal such things as the proud use by directors of their own bodies in the collection they once directed.15 Anatomical displays need to be set within vastly complex social and cultural practices that included not only science but also fears and pleasurable shivers over premature burial, security coffins, mesmerism, coma and somnambulism shows, hysteria demonstrations, and social and artistic preoccupations with beautiful death that found expression not only in the anatomical museum but in art and the vogue for mortuary photography. The staging practices of museums need to be read within vast realms of public entertainment that included public morgue visits in nineteenth-century France, wax museums, fantastic and horror literature, mummy parties, and Cafés of the Dead in Paris and at the 1907 St. Louis World’s Fair.

One might open the Fragonard collection for a new public at night to read Maupassant’s fictional tale of a dried hand that wanders, seeking the man who severed it, and the real story of writer who used a dried hand as a decorative piece.16 It could be a place to offer lectures on the history of cafés of the dead, and beliefs in the wandering dead, to let texts, fairground posters, photographs, and excerpts of plays tell the history of the pleasures the living once took in their association with the dead.

Today might be the perfect time to reexamine our relationship with the dead bodies of the anatomical museum. With tens of millions of people around the world having already paid to see plastinated humans posed in extremely theatrical poses from card- and chess-playing specimens to specimens jumping, running, diving for volleyballs, conducting imaginary orchestras, doffing a hat, or holding their brain in their own hand astride a giant rearing plastinated horse, the older bodies of the anatomical museum–the dancing and turban-wearing fetuses perhaps apart–are hardly shocking or unsettling. There are moments when necro-fantasies run deeply through Western culture. Because we seem to be in one of those moments now, it could be possible to draw the public into the older ones again, through permanent or temporary exhibitions that let the public walk not past the bodies, but through them into the complex worlds of history, fairground history, art, and literature that they once inhabited.

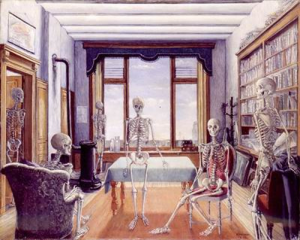

Figure 12: Paul Delvaux. Waiting for the Liberation (Skeletons in an Office), 1944

Where they could go on their walks can be a sometimes pleasantly macabre world that the museums occasionally shared with writers of fantastic literature and horror fiction. It can also be a world full of strange beauties; of sensitivity to bodies, suffering, and the fragility of the human condition generally. The Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh brought in poets who created lovely works of poetry in the places of bones, bits of bodies, and instruments.16 I think the pathological collection in Edinburgh should be opened to the public again, with the poetry not only posted by the bodies, but occasionally read in their company. Poetry and short story readings in the anatomical museum could bring in new publics whose contact with the anatomized could be softened and filtered through the lilt of poetry and the enjoyment of tale-telling. The just barely-rescued Spitzner collection of medical waxes that once toured Europe for more than a century, that disappeared in the mid-twentieth century, was rediscovered (partially), restored, and taken to Paris, has never been brought back into public view, except for brief and partial moments. This spectacular collection which provides an invaluable window onto the popular experience of fairground anatomy and ethnology has just been moved into storage. It is a terrible loss not only of popular medical history, but of the objects that had a profound influence on the art of Paul Delvaux. Delvaux’s visual reveries of nudes and skeletons that sit down on sofas and chairs to converse or wander off into sunlit ancient worlds or down darkened Belgian streets, are part of a complex history of bodies. Both the bodies and the history belong to no single discipline. Delvaux’s wandering skeletons are products of the places where anatomical and natural history museums, fairgrounds, and art met (Figure 12).17

It would take funding to create interdisciplinary exhibits that could cross the spaces of art, history, and medicine. It would take the willingness of museums to share artworks and anatomical objects and to reconceive some of their spaces and the ways in which they treat message-making within the museum. Story-telling and pedagogical message-making need not be impossible bedfellows in the anatomical museum. It would mean conceiving of museums not as spaces of a single discipline, rising like a pillar, but as a horizontal places; places of connections where the public might see skeletons who sit down to converse, and through them, what wanders along the borders of the disciplines.

Biography

Kathryn A. Hoffmann is professor of French at the University of Hawai’i, Manoa. She is the author of Society of Pleasures: Interdisciplinary Readings in Pleasure and Power during the Reign of Louis XIV (St. Martin’s 1997) which was awarded the Modern Language Association’s Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for French and Francophone Literature. She has published work on literature, art, history, and the history of medicine. Her books in progress are tentatively entitled Phantasms of the Feminine and Processions of Venuses.

Acknowledgements

This essay would not have been possible without the generous assistance of the museum directors and staff who permitted access to collections, provided photographs or permissions, or accompanied me during visits. They are thanked, along with the photographers who shared their images.

Endnotes

1. Some museums considered historically important–and thus important to maintain in their historical form—do integrate pathological specimens into broader collections. Museums that do this include: Hunterian (Glasgow), Musée Dupuytren (Paris), the Musée Vétérinaire d’Alfort (Paris), National Museum of Medicine (Washington, D.C.). In the National Museum of Medicine in Washington, D.C, the fetal specimens on display are a tiny part of a large collection of wet specimens in storage, assembled from closed collections throughout the country.

2. ‘Currently major development of the Pathology Museum is being planned to allow greater public access to this collection of international importance’ (Surgeons’ Hall Pathology Museum).

3. The Musées Delmas-Orfila-Rouvière and the Collection Spitzner at the Université de Paris-Descartes. The museums are in storage as of March 2010.

4. ‘Tout entier à ces préoccupations anatomiques, il [Fragonard] imaginait, inventait des pièces qu’il désirait fort qu’on vînt voir, mais il n’écrivait rien, et on eut pu dire de lui, comme on disait de Ruysch qu’il parlait aux yeux; aussi répondit-il à ceux qui lui parlaient de son cabinet: venez et voyez’ (Thouret, cited in Lemire, 1990; 172). All translations, unless otherwise indicated, are mine.

5. I discuss Desnoues and Ruysch in ‘The Theatrical Cadaver’ (2008).

6. The most important collection of eighteenth-century models, copied for museums throughout Europe, is in Florence, at the Museo di Storia Naturale, Universita di Firenze, Sezione Zoologia, known as ‘La Specola’.

7. For images and the history of the piece and its transfer to the Ecole des beaux-arts, see Comar (2008; 174) and a brief mention in Fend (2008; 2).

8. Harry Brookes Allen Museum of Anatomy and Pathology. The reference to the “late” Dr. Sue and the purchase date of 1862 suggest it was Jean-Jospeh Sue the second (1760-1830).

9. Images are found in Le Cere del Museo dell’Istituto Fiorentino di Anatomia Patologica (n.d).

10. For an inverted bronchial tree as art, see Michael Christian, ‘Bronchial Tree’ (2000).

11. ‘Les préparations pédagogiques se consacrent à l’étude d’un appareil bien précis; leur rigueur et l’absence de mise en scène les différencient facilement des autres Ecorchés, figés dans la mort dans des attitudes théâtrales’ (Musée Véterinaire d’Alfort, ‘La technique de préparation des écorchés’).

12. ‘L’esprit frivole de la nation ne se manifeste-t-il pas, même lorsqu’elle entreprend quelque chose de réellement grand et noble, alors que devrait s’effacer son caractère badin et folâtre.’

13. ‘Toutes leurs préparations, rassemblées dans le cabinet, satisfont seulement la vue; peu d’entre elles peuvent servir à la démonstration de nouvelles vérités… partout ce sont des raffinements qui ne sont pas instructifs.’

14. See Jonathan Simon (2002, 2008) and Yvonne Poulle-Drieux (1962).

15. I am working a piece on the incorporation of the remains of museum directors in a nineteenth-century Italian museum.

16. Guy de Maupassant wrote two stories on a murderous dried hand: ‘La main d’écorché’ (1875), and ‘La main’ (1883). On the origin of the hand, which Maupassant wrote had originally belonged to the poet Swinburne, see Maupassant’s ‘L’anglais d’Etretat’ (1882).

17. See Conn (2002) and Hoffmann, ‘”Vertebrae on Which a Seraph Might Make Music”‘ (2010; 152-160).

18. An essay on Paul Delvaux and the Spitzner Collection is in preparation. I discussed the Spitzner, with brief remarks on Delvaux, in ‘Sleeping Beauties in the Fairground’ (2006; 139-159).

References

Bann, Stephen. ‘Poetics of the Museum: Lenoir and Du Sommerard’ in Donald Preziosi and Claire Farago, eds., Grasping the World: the Idea of the Museum (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2004), 65-84.

Le Cere del Museo dell’Istituto Fiorentino di Anatomia Patologica (Firenze: Arnaud Editore, n.d.).

Christian, Michael. ‘Bronchial Tree’ (2000) photograph by Salvatore Vasapolli, http://images.burningman.com/index.cgi?image=1055

Comar, Philippe (ed.) Figures du corps. Une leçon d’anatomie aux beaux-arts [exposition, Ecole nationale supérieure des beaux-arts de Paris, du 21 octobre 2008 au 4 janvier 2009] (Paris: Beaux-arts de Paris les editions, 2008).

Conn, Stuart (ed.) The Hand that Sees: poems for the quincentenary of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (Edinburgh: Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, 2005).

Didi-Huberman, Georges, Ouvrir Vénus: nudité, rêve, cruauté (Paris: Gallimard, 1999).

Fend, Mechthild. Review of Exhibition: Figures du corps. Une leçon d’anatomie aux beaux-arts. Paris, École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris. 21.10.2008-04.01.2009 ArtHist (December 2008): 1-3. http://www.arthist.net/download/expo/2008/081222Fend.pdf

‘Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva’, Genetics Home Reference, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition=fibrodysplasiaossificansprogressiva

Hoffmann, Kathryn A. ‘Sleeping Beauties in the Fairground: The Spitzner, Pedley, and Chemisé Exhibits’, Early Popular Visual Culture 4:2 (July 2006): 139-159.

—–. ‘The Theatrical Cadaver: Staging Death in the Seventeenth Century’, CESAR/Clark Symposium, 2008, http://www.cesar.org.uk/cesar2/conferences/conference_2008/hoffmann_08.html

—–. ‘”Vertebrae on Which a Seraph Might Make Music”‘, PMLA 125:1 (2010): 152-60.

Lemire, Michel. Artistes et Mortels (Paris: Chabaud, 1990).

Maupassant, Guy de. ‘L’anglais d’Etretat’, Le Gaulois (29 novembre 1882): 1.

—–. ‘La main’, Le Gaulois (23 décembre 1883): 1.

—–. ‘La main d’écorché’ L’Almanach lorrain de Pont-à-Mousson, 1875 (signed Joseph Prunier).

—–’La petite Roque’, in Contes cruels et fantastiques (Paris: Librairie Générale Française 2004).

Musée Véterinaire d’Alfort, ‘The Ecorchés by Fragonard’, http://musee.vet-alfort.fr/Site_GB/index2.htm

—–. ‘La technique de préparation des écorchés’, http://musee.vet-alfort.fr/Site_Fr/index2.htm

Museo di Storia Naturale, Università degli Studi di Firenze, Sezione Zoologia, http://www.msn.unifi.it/CMpro-l-s-11.html

Nesi, Gabriella, Rafaella Santi, Gian Luigi Taddei, ‘Art and the Teaching of Pathological Anatomy at the University of Florence since the Nineteenth Century’, Virchows Archiv 455:1 (2009): 15-19.

Panzanelli, Roberta (ed.) Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2008).

Pirson, Chloé. Corps à Corps: Les Modèles anatomiques entre art et médecine (Bruxelles: Maure et Martin, 2009).

Poulle-Drieux, Yvonne. ‘Honoré Fragonard et le cabinet d’anatomie de l’École d’Alfort pendant la Révolution’, Revue d’histoire des sciences et de leurs applications 15 (1962): 141-162.

Simon, Jonathan. ‘Honoré Fragonard, anatomical virtuoso’, in Science and Spectacle in the European Enlightenment, Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Christine Blondel eds., (Aldershot, Ashgate, 2008), 141-158.

—–. ‘The Theater of Anatomy: The Anatomical Preparations of Honore Fragonard’. Eighteenth-Century Studies 36:1 (Fall 2002): 63-79.

Surgeons’ Hall Pathology Museum, Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, http://www.museum.rcsed.ac.uk/content/content.aspx?ID=11

Thouret, Michel-Augustin. ‘Compte-rendu du décès de Fragonard, 19 germinal an VII (8 avril 1799)’, in A. Prévost, L’Ecole de Santé de Paris (1794-1809) (Poitiers: 1901), 135.

Von During, Monika, Marta Poggesi, Georges Didi-Huberman. Encyclopaedia Anatomica: A Complete Collection of Anatomical Waxes. Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università di Firenze (Köln: Taschen, 1999).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.