Abstract: In The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rosch argue that our perception of a given colour is not only relative to its environment but to the continuous interaction between the human perceptual system and its environment. Thus our cognition of colour in the world cannot be attributed simply to wavelengths and intensity of reflected light nor to some given neurobiological system that we possess. (Varela et al, 1991).Further, Alva Noë, the philosopher of mind, claims that human perception can only occur through action and that this “enactive approach” requires perception to be determined not simply by an isolated visual system but by acquired sensorimotor knowledge (Noe, 2004).Accordingly, what we are presented with is a model of cognition-perception that requires “skilful bodily activity”, what has now become known as enactive cognition.

This paper considers the implications of embodied perception within, broadly speaking, the field of new media arts practice; both in its creation and reception. I argue that within some facets of new media practice the frontal projection screen is still given primacy, and draw upon the recent interest in the potential of dome cinema as a primary example. In focusing the discussion on a comparison between historical church and contemporary planetarium dome environments, I will discuss the work of baroque painter and architect Andrea Pozzo in relation to contemporary moving image dome projects. I will argue that the trompe-l’oeil of Pozzo’s work presents a useful framework for thinking through enactive cognition for new media environments and the necessity of moving away from a traditional cognitivist model of perception.

This paper considers the implications of new research done within the area of cognition and perception and how this can possibly contribute to a rethinking of some aspects of both the creation and reception of new media art. Firstly, I need to introduce some of the key concepts in the field as they relate to my argument.

In Blow-Up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain, artist Warren Neidich builds on Gilles Deleuzes’s idea of cinematic time and space, and, when discussing the optical impacts of photography and cinema, suggests that there is constant feedback between the brain/subject’s ordinary motor-sensory experience and what is given to them to perceive by the technologies of any given period.

These optical inventions feed back on culture itself, changing its face in the context of this new view of itself, as well as feeding back on the brain through their effect on networked relations in the real world and the brain’s response to them. (Neidich, 2003: 35)

Neidich’s work is an acknowledgement of feedback that shapes the brain: its constant re-orientation to its environment via a particular period’s technologies’ impact upon our perceptual systems.

Neidich is not the only one proposing that cognition and perception are open to their environment and here we must briefly look at particular work within the cognitive sciences that question traditional models of perception. In The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience, Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rosch argue that our perception of a given colour, for example, is not simply relative to its environment but arises out of the continuous interaction between the human perceptual system and its environment. (Varela, Thompson and Rosch, 1991: 157). Thus our cognition of colour in the world cannot be attributed simply to wavelengths and intensity of reflected light nor to some given neurobiological system that we possess. What is being challenged here is the idea that perception is somehow a pre-given: either that it is genetically hardwired and we simply know how to perceive, or that as information comes in, we cognitively adjust and respond accordingly. What Varela and colleagues are suggesting is that yes, we do respond on a cognitive level to input from our environment, but that we are active in changing that environment as a result. An active coupling of organism and world takes place, which they call ‘structural coupling’, and this produces both an enactive perceptual system together with its environment (Varela et al, 1991: 151, 164-5).

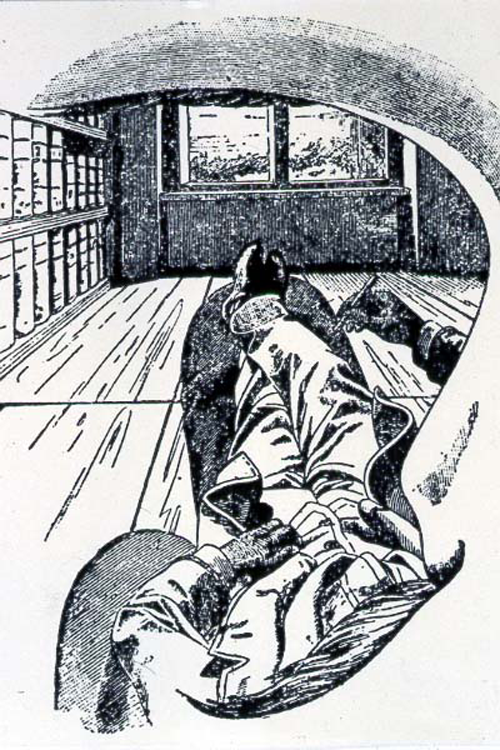

Further, Alva Noë, a philosopher of the mind, claims that human perception can only occur through action and that this ‘enactive approach’ requires perception to be determined not simply by an isolated visual system but by acquired sensorimotor knowledge (Noë, 2004: 1-2). This is not about a model of the world in the head (that is, mental representations preformed by the mind), nor is it about attributes already existing in the world that we receive like imprints onto the retina or other sensory organs. If, as Noë goes on to claim, we consider sensory perception on a predominantly visual model, the eye is often compared to a camera and what you have — as in Ernst Mach’s example of attempting to draw his own visual field where the entire depth of field is rendered perfectly in focus — is the world in high-definition and in sharp focus from the centre to the periphery (Noë, 2004: 35). This simply does not happen in actual seeing.

Ernst Mach, Picturing the Visual Field, 1886

Instead, as Noë suggests, peripheries are blurred and these blurred areas become the regions the eye actively seeks out and scans in order to bring the world into focus. Visual perception is therefore accompanied by activities of the sensory-motor apparatus and, in connection with its environment, the human perceptual system actively produces a visual field/world. This is a way of thinking through cognition that identifies a “world” brought forth or enacted by the embodied relations sustained between humans and their environments. Accordingly, what we are presented with is a model of cognition-perception that requires “skilful bodily activity”; what has now become known as “enactive cognition”.

These intertwined models of perception presented by Varela and Noë are radically different to traditional cognitive approaches in that they both argue the importance of a lived experience in relation to perception. In conjunction with Nedeich’s argument of the role of technology in shaping the brain, I would suggest that they offer a rethinking of what I will call the problem of the “framework” of some new media practice. Much of the technical delimitations of working within digital media technologies remain “framed”: 16×9, 4:3, screen resolution and so forth. Visuals are captured via various cameras, or developed solely within the environs of computing systems and output is, to a greater extent, consistent with the format and ratios that the input systems dictate. Thus, even large scale, multi-channel projected video works comply with this framework model. Within this framework, the image is moving and the viewer, even if she is an active participant in some sense, remains relatively static with respect to the frame. This is not to infer that they do not move around a space — generally, depending on the scale or location of pieces within an installation they will. But I would argue that they are moving in relation to the frame — even when works appear un-framed by the use of multiple screens.

There are of course exceptions to this — Patricia Piccinini’s Swell (2000) for example, in which the unstable horizon of the moving water within the screen-based image, shifts attention away from a visual-frame model of perception to incorporate something outside the screen — internally induced sea-sickness in the viewer.

Another aspect of this work that warrants attention is the minimal use of movement: the work’s potential is linked to a person’s movement within the space rather that operating with the assumption of bodily stasis. But these kinds of art practice examples nonetheless remain exceptions to an overall framing of the new media image.

So my question is, how does one un-frame a work and importantly, for what purpose? In order to address these questions I would like draw a line from a concept taken from Baroque aesthetics — “double perception reality” — which comes to us via a discussion of the vaulted ceiling of Saint Ignazio’s Cathedral in Rome. I hope to use this concept in relation to examples of new media projects and their associated technologies, particularly contemporary dome-based works. I will suggest that an enactive understanding of visual perception was embedded in the creation of Baroque domes and that we might draw on this practice, along with newer ideas about perception-cognition, to un-frame or rethink aspects of contemporary media arts.

The Baroque monk, artist and architect Andrea Pozzo designed the fresco in St. Ignazio’s, the Triumph of St. Ignatius of Loyola, completed in 1694. It is regarded as one of the defining examples of the quadratura style. Unlike the tromp l’oeil style traditionally associated with painting, whereby the artist relied on intuitive methods to create a deception of sorts — for example, of illusionistic architectural facades on painted surfaces — quadratura created the appearance of a three-dimensional space within a two-dimensional image in a much more precise manner, based on seventeenth century theories of perspective. Within the Baroque period, an understanding of perspectival drawing and foreshortening joined to create an architectural illusionism whereby the real architectural aspects of the space converge with the painted ones — each medium’s edge disappearing. This spatial relation between architecture and painting is what John Macarthur identifies as a double perception reality (Macarthur, 2002:6).

Further, according to Macarthur, Pozzo:

…introduces a third state. The image appears, geometrically and mentally, a perspective projected onto to the flat screen of the picture plane, but it is in fact painted onto the complex curved surfaces of the vault and cross vault that have a phenomenal depth– even though this is unlike that represented in the image. Thus, the phenomenal depth of the curved picture surface is a kind of perceptual approximation of the illusory depths of the notionally flat image.” (Macarthur, 2002:8)

As seen from below, di sotto in sù, essentially what one experiences when walking through the vaulted space of this Baroque dome is a narrative unfolding. Here is an architectural space that is both around and above the viewer. New elements come in to focus as others begin to recede or distort as they become peripheral. The experience is not of walking through a space that happens to be a dome, but rather of following the architectural lines of sight up, moving one’s body toward the point where there is finally — both visually and allegorically — a break in the clouds. Continuing to move towards the vaulted space, you discover a shaft of light from above, and it is only when directly underneath the central dome space that you are aware that it is not an architectural dome at all: it has in fact been painted onto a flat ceiling — 17 meters in diameter. In fact Pozzo’s masterpiece of Baroque dome painting, St Ignazio’s, doesn’t have a dome at all due to developmental zoning issues in the seventeenth century.

The fresco is designed to line up with a central point in the cathedral– marked with a gold star embedded in the floor of the nave — where we are able to fully appreciate a finally visually-centralised God addressing Ignatius and framed by saints from the four continents. If we are indeed framed in this space it is the very physical architectural elements themself that frames our view: walls, doors columns and windows.

Hence the double perceptual reality of the image is not simply an oscillation of the image between the real and the illusionistic but, more importantly, the oscillation of visual perception between and toward the entire human sensory-motor apparatus that enables the moving-image. The Baroque dome, although ultimately committed to perspectival visual orientation, nonetheless enables us to see the indebtedness of visual perception to the body’s active movement through space — to the ways in which this perspective only comes into focus as a result of bodily action on the part of the viewer.

Much contemporary exploration of un-framing has been within a cinematic context. Every new technological development in film is geared ultimately towards the viewer’s experience. It is not done, however, through consideration of the image’s double perceptual reality, but rather through attempts to abolish a dimensional boundary, or frame, by creating a larger projection throw. One of the pioneers of Imax, and now Dome cinema, Ben Shedd, describes it thus:

I think one of the quickest ways to describe this new cinematic world comes from Roman Kroiter, one of the founding members of the Imax Corporation and a first generation giant screen filmmaker. Roman suggests putting a cardboard box over your head with a rectangular shaped hole cut out from its bottom. Look through that rectangle. That is the view of the movies, of TV, of small screen cinema as we have come to know it. Then take the box off your head. That’s the gigantic screen view. Unframed cinematic visual space. (Shedd, 1989)

For Shedd, when the action is projected so large that it moves beyond our peripheral vision we have essentially, ‘exploded the frame’. In referring to his own practice he informs us that he is creating an ‘architectural experience’ and that:

In accounting for the sensation of movement, the filmic experience has moved from passive, from being held in a frame, to active, to becoming the engulfing reality with the audience present within the filmic events. In frameless film the audience becomes the main character in the film. (Shedd, 1989)

In setting up my argument I used the example of Baroque domes, and thought it appropriate to follow through with a look at the still evolving field of full-dome projection — customised cinematic projections designed for a domed environment. In much full-dome work, the Point of View (POV) is a singular position opposite the projector that immediately placed the viewer in the traditional cinematic position of looking directly ahead. The problem in this instance, however, is that we are aware that some visual aspects are in fact occurring outside of our perceptual field but as we are lying on the floor (or sitting in a cinema type environment) it is not possible to move around.

In February 2009, as part of the Adelaide Film Festival, the Mawson Lakes Planetarium on the outskirts of the city played host to The Best of Domefest, works selected from the international festival held annually in Albuquerque New Mexico and curated by its founder David Beining. The singular POV was pervasive within the overall program of films shown, with some exceptions. The work Centrifuge, as its names suggests, made full use of its visual environment: there was no central place to fix the gaze as the entire dome displayed the movement of the centrifuge rapidly increasing in speed and circling the circumference of the dome.

The use of dome environments for the display of visual art is not recent — in 2002 the French filmmaker Jean-Michel Bruyère developed Si Poteris Narrare, Licet in conjunction with the Extended Virtual Environment (EVE) by Jeffrey Shaw, ZKM and the iCinema Centre for Interactive Cinema Research. On one level, the work does make use of the entire domed space, however, the work is generally experienced in fragments, that is, only partial elements or squares of the work can be seen at a given moment. Further, participants are subjected to a large centrally located navigational device designed to interact with the work. So, whist the audience is encouraged to actively move around the space, the constant disruption of many people controlling the narrative results in a fragmentation of the space that undermines any individual attempt to experience a full-domed environment.

This is a still developing field however, and there are some interesting new works being made utilising the dome environment and peripheral-visual space that might un-frame new media and orient it towards a more enactive form of cognition. A recent residency project between Australian artists John McCormick and Adam Nash involves creating a ‘reliable technical framework that allows for the future development and staging of a compelling “mixed reality” performance/installation work’ (McCormick and Nash, 2009). Their present work in progress relies on the movement of people within the domed environment in order to create the interaction and evolution of the piece. Arguably, the artists’ ongoing work within the fields of multi-user virtual environments, motion capture and installation environments will result in a greater level of consideration of visuals, sound and, importantly, movement with the space.

Perhaps fittingly, it is useful to consider work that returns to the origins of the planetarium — space. In Celestial Mechanics (data collection on the mechanical sky), 2005-2010, Scott Hessels, in collaboration with Gabrielle Dunn, attempts to visualise the data of a constantly changing stratosphere. According to Hessels:

…many of the machine behaviors and patterns in the artwork are already part of our semiotic language. The shaky blue circle of light from a police helicopter is as culturally coded as the military planes flying in perfect V formation, the stacked planes over LAX, and the melancholy dissipation of distant jet trails. Just like the mythologies created centuries ago by seeing patterns in the stars, we again are applying cultural significance to pattern and new ‘constellations’ are being formed by airborne machinery. (Hessels, 2009)

I would argue, by way of conclusion, that the contrast is not between “old media” such as traditional cinema and “new media” such as Imax or Dome cinema that somehow, due to the technologies of surround sound and screen size suddenly allow us to be immersed and therefore active/or enactive characters in a film. Rather the contrast is between different understandings of perception and how these might be incorporated into the practices of screen-based media, cinema and spatial design. If we can have enactive perception operating in a medium such as painting when it converges with the space of the Baroque dome, then it is not simply the march of new media technologies that will make us active participants. Instead we should look at the ways in which new media environments do or don’t allow for the production of an enactive perceiver.

Biography

Dr Michele Barker works in the field of new media arts, exhibiting nationally and internationally. Her work addresses issues of perception, subjectivity, genetics and neuroscience. Works include the CD-ROM, Præternatural, selected for exhibition in ‘Vidarte‘, the Mexican Biennale of Electronic Art, 2002 and ‘Contact Zones’ a touring exhibition of CD-ROM art in 2001. The work is now in held in the Rose Goldsen Archive of New Media Art, Cornell University. In 2004, she held an Artist-in Residency at Eyebeam New York. She developed the award winning multi-channel work, Struck, which has been exhibited in Australia, the US and China. Barker’s research has been presented at major international conferences including ‘Future Bodies‘, Cologne, ‘Vidarte‘ Mexico and ‘New Constellations: Art and Science‘. She is presently working on an immersive dome project as well as investigating the relationship between the neurosciences and magic. Barker is a senior lecturer at the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, Australia.

References

Stalder, Felix and Hirch, Jesse. ‘Open Source Intelligence’, First Monday 7.6 (2002), http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue7_6/stalder/index.html

Hessels, Scott. ‘The Machines above us: An overview of the “Celestial Mechanics” new media art work’, MutaMorphosis (2009), http://mutamorphosis.wordpress.com/2009/03/02/the-machines-above-us-an-overview-of-the-celestial-mechanics-new-media-artwork/

Macarthur, John, ‘The Image as an Architectural Material’ South Atlantic Quarterly (Duke University Press), vol. 101, no. 3 (‘Media Auras’), (2002): 673-693

Neidich, Warren, Blow-Up: Photography, Cinema and the Brain (New York: D.A.P., 2003)

Noë, Alva, Action in Perception (Cambridge, Mas.: The MIT Press, 2004)

Shedd, Ben, ‘Exploding the Frame: Seeking a new cinematic language’ (1989), http://web.mac.com/sheddproductionsinc/www.sheddproductions.com/Shedd_Productions,_Inc._EXPLODING_THE_FRAME_Papers_&_Essays/Entries/2008/10/27_Original_EXPLODING_THE_FRAME_article_-_Written_1989.html

Francisco J. Varela, Evan Thompson and Eleanor Rosch. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (Cambridge, Mas.: The MIT Press, 1991)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.