This brief paper was inspired by a presentation In April 2008 where, as the General Manager of the Australian Network for Art and Technology (ANAT), I addressed a CHASS workshop on Art and Innovation. After the presentation it became apparent that ANAT, in some ways, had been charting its own course in answering the question of the best way to get innovation from creative pursuit. ANAT had been using internal models that had been developed to help guide the organisation and these models were not being used outside of ANAT. One of the main concepts that highlighted a point of difference was a concept I had developed of Ancillary IP’s.

Ancillary IP’s

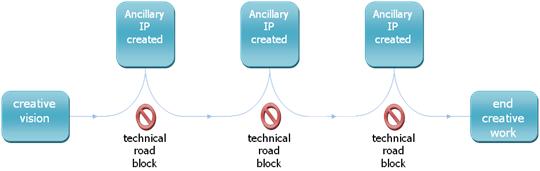

Diversifying creative practitioner revenue streams through a review of the full range of IP developed in creative practice has lead me to develop a concept of Ancillary IP’s at ANAT. Ancillary IP’s occur when, in the course of a practitioner pursuing their vision of a final work, they encounter difficulties that require the development of a technology, device, process or code. This is particularly evident with those who use emerging technologies, but can be translated across many areas of the arts, the broader creative industries and arts organisations.

Ancillary IP Creation

A Simple Case of Ancillary IPs

KneeHIGH puppet performance group is involved in large scale puppetry that often involves performance artists manipulating puppets from inside the puppet structures. For safety and ease of use they design and manufacture a unique stilt design. This case shows how artists in pursuit of the end creative work have created an Ancillary IP. This has the potential to be licensed to other performance companies or as a toy for general consumption.

The Benefits of Ancillary IP’s

Ancillary IP’s end up falling somewhere between innovation and invention due to the unique research and development environment in which they occur. Ancillary IP’s are not an intended end result for the practitioner – the end result always remains the creative vision for the work – but the Ancillary IP’s are created to resolve a specific ‘roadblock’ that the practitioner has encountered in the pursuit of that vision. As such, Ancillary IP invention goes beyond the mere ’good idea‘ stage at which many inventions stall. There is an in-built resolution of a real problem in the invention. This halfway line between innovation and invention means there is a higher chance of finding like applications beyond the creative work, making for a very efficient research and development model for innovation.

The Case of Designer as an Innovation Consultant

In the 2007 AIR residencies undertaken by ANAT with funding from Arts Victoria Leah Heiss a designer undertook a residency with Nanotechnology Victoria. With in a three month period this collaboration ended in a patent application for a water purifying unit worn against the body.

http://heiss.anat.org.au/

Ancillary IP’s are created in the pursuit of a creative goal. There is no intended practical application predefining outcomes. This pure intellectual curiosity and personal vision combined with the creative drive gives rise to Ancillary IP’s generated in a milieu of boundary redefinition. This unbounded intellectual pursuit is in danger of being overlooked in many structured research and development environments. Ancillary IP’s take advantage of this process by encouraging serendipitous unexpected outcomes.

Current Situation

Traditionally this IP has been either given away, or it has remained under utilised, with the exception being in the realisation of an artist’s final work. Artists are not necessarily trained to look for these opportunities and there is an asserted strong culture of discouraging entrepreneurial drive out side of the traditional exhibiting and sales. This aversion though is often not played out in reality and once the concept of Ancillary IP’s is explained to practitioners they are quite comfortable with pursing it, but they lack the basic understanding of how.

In many ways, the dormancy of Ancillary IP’s stems from a lack of recognition that they exist. Those who would be interested in the possible commercial outcomes that Ancillary IP’s can generate are not aware that they can be found and creative practitioners are either oblivious to its existence, or the significance is lost in the context of the final creative work.

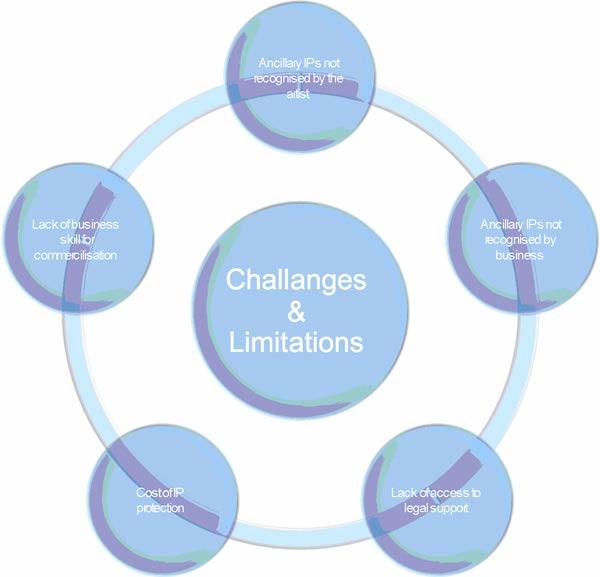

Challenges & Limitations

The challenge is first to recognise the creation of these Ancillary IP’s. They exist, but are often overlooked as important creations in their own right. Recognition is low because those working in the field have a lack of expertise and knowledge of business, innovation strategies and general entrepreneurial ways of approaching their work. Research by Gasgoine and Metcalfe (2005) found that those working the arts “cited their own lack of business skills as an impediment”. While many creative practitioners are skilled in the marketing and sale of work, their engagement with mainstream business is low (Comunian 2008). Comunian (2008) goes on to argue that business engaging with the arts on a sponsorship or philanthropic model is only now gaining credibility. So to suggest a collaborative research and development relationship between business and creative practitioners would be pushing these relationships much further then they currently exist.

Once recognised, further challenges need to be overcome. Access to the legal support to protect Ancillary IP’s and the entrepreneurial business skills and contacts to develop them into revenue are both limitations. In the arts there is a great deal of information with regard to copyright, but very little skill and knowledge around the protection of Ancillary IP’s. Protection through patents are costly.

IP Australia states “The average estimated cost of an Australian standard patent, including attorney fees, is between $6,000 to $10,000, depending on the complexity of your application. This cost is only to be used as a guide, you should contact a patent attorney for specific advice on your circumstance. Maintenance fees over a 20 year term would be a further $8,000.”

http://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/patents/fees_index.shtml

This does not cover the cost of any legal advice, plan documents and prototypes and international patent requirements. The arts sector is starting from a low base in the capacity to fund such ventures. Professional firms in many areas are very generous to the arts and creative practitioners in terms of pro-bono work, but this emerging market is alien. The sense that this is purely commercial and therefore a purely fee for service proposition is understandable, but this is a new market that needs to nurtured and strengthened.

The protection of Ancillary IP’s gives an artist choice. They may choose to freely share their IP or they can chose to protect it; to either exploit it or hold on to it for possible opportunities into the future. These choices can only truly be made by thinking of the business models needed from the beginning. The patenting of IP is of no value unless there are strategies in place to commercialise.

Opportunities

Ancillary IP’s appear everywhere. There are real opportunities for business to fill the skill void and work with practitioners to bring this IP into the mainstream and envision ways of making them commercial.

There is a need for entrepreneurial skills to be taught to creative practitioners. The traditional route of sourcing grants, exhibiting and making gallery sales only keeps a small group of creative practitioners employed and even then the need to seek other employment in areas like hospitality and administration occurs. Those engaging in new creative expression find that the traditional markets do not cater to their form of output. Consequently, the ability to develop an entirely different revenue stream than what has traditionally been acceptable is pressing.

For business there is an enhanced capacity for generating unforseen products. Engaging with creative practitioners to help them develop Ancillary IP’s can open up a new way of outsourcing research and development. This consultative approach to using creative practitioners can extend to research laboratories and take advantage of practitioners working in areas as diverse as biology and robotics.

The challenges are not insurmountable and the benefits of engaging with the innovative potential in creative practitioners work are enormous for the arts sector, creative industries and the broader economy. These Ancillary IP’s create real opportunities to develop revenue streams beyond the sale of creative work.

Conclusion

It is hoped that in presenting the Ancillary IP’s model a broadening of the economic scope for creative practitioners arises. Artists, arts organisations, research laboratories and businesses can benefit from a model in which they can recognise the existence of IP and generate new revenue streams without compromising creative practice.

Artists are creating Ancillary IP’s now. It is not a wheel that needs to invented. Ancillary IP’s need to identified and the business opportunities nurtured.

Gavin Artz

Gavin Artz, ANAT CEO has extensive experience in business management, governance and finance from multinational organisations to not for profits entities.

References

Comunain, R., 2008, Culture Italian Style: business and the arts. Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 29. No.3, pp. 37-44

Gascoigne, T. & Metcalfe, J. 2005. Commercialization of research activities in the humanities, arts and social sciences in Australia. CHASS Occasional Papers, No 1. May.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Australia.