Over the last century, automation has been presented as a means to liberate the human soul from dreary and repetitive work. Building machines that operate themselves allows us more time to be what we are – humans, with a need to create, interact and seek pleasure.

So what happens when these desires are sourced from or with a machine? From artists working with new technologies to the mass of human labour invested in creative work, we see an interesting repositioning of identity occuring between humans, technology and the economic market.

Purple Error © David Szauder 2010. Used with permission of the artist.

In the fine arts, the relationship between artist and machine appears straightforward. The computer’s ability to rapidly and reliably complete certain tasks maximises the creative potential of the artist. The machine becomes an integral, though slave partner to the human virtuoso. However this relationship quickly becomes more complex when you consider, for example Glitch artists who work specifically by provoking unexpected results from the audiovisual capacity of their machines. This capacity might be considered the machine’s own potential for creativity, merely coaxed into action by the artist.

Although the economic value of this type of creative labour is mostly insignificant, the spread of communication technologies is contributing to its worth. Documentation of artistic events existing in the public domain, for example video and sound recordings uploaded by audience members, creates a new mass of virtual capital. While freely accessible, this documentation generates the artist future wealth (bookings) and also contributes to the wealth of associated peoples (venues, curators, festivals). In doing so it merges with the flood of advertising and other more recognizable outputs of creative industry professionals that saturate our media.

Interestingly, the creation of this capital is not undertaken by people aware that they are involved in any kind of work. Communication technologies have so pervasively infiltrated our leisure-time that it is hard to draw definitive lines between action, relaxation and labour.

Millions of people worldwide contribute hours of unpaid work supplying personal information to advertising and marketing companies through platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. These platforms are based specifically on their users’ identity. As human activity and interaction is increasingly carried out online, our definition of self begins to blur, morphing into something called ‘data’; sets of specific information describing where and how we live, think and act. This information is recordable, quantifiable and very, very useable as an economic resource.

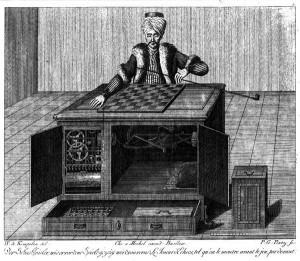

In addition, multitudes of people choose to work for obscenely low wages performing Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs) as part of online crowd-sourcing systems. Crowd-sourcing works by distributing small, menial tasks across vast numbers of online human workers. The first such example was Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, named in reference to one of the earliest recorded automatons which reportedly utilises over 10,000 workers in 100 different countries.

The Mechanical Turk: Wolfgang von Kempelen 1784. Image in the public domain.

The original Mechanical Turk was a chess-playing machine that toured Europe and America in the late 18th to early 19th Centuries and was eventually revealed to be a fake controlled by a hidden human operator. As an Amazon Mechanical Turk, your job is typically to complete tasks that the computer is not yet able to do effectively. For example, a computer running an online shopping system cannot easily distinguish between two similar product images varying only in colour, yet the human eye can accurately and instantaneously make this distinction and tag the image with the appropriate data.

And so we arrive at a complete reversal of our previous understanding of the role of machines in our lives. Instead of automated machines allowing us to live more humanly, we have networks of humans helping computers carry out their tasks more effectively, thus becoming better machines.

In the creative industries and increasingly everyday life, the harnessing of computer technologies turns the elements most fundamental to human life; creative expression, cognitive reasoning and social activity into an economic resource. Machines have evolved far beyond labour-saving devices to become a preferred means of self expression and, indeed, extensions of our very selves. Technology certainly enables us to live our lives more productively, however of which product we are speaking and exactly how much of our lives it inhabits is unclear.

Lucy Benson

Lucy Benson is an Australian media artist & designer based in Berlin.

See More

http://pixelnoizz.wordpress.com

Read More

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/31/business/31digi.html

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Australia.